Look Mum, No Breakpoints!

I always found responsive design challenging. I'd start with two designs, one for mobile and one for desktop, but I then needed to work out how to get from the mobile design to the desktop version. Which involved creating designs for each breakpoint between the two main designs.

It was a slow and frustrating process.

And to be honest, the results were underwhelming. Everything was too big and close together at the start of each breakpoint - and too small and far apart at the end of it.

I thought the only option was to add more breakpoints, then I stumbled across Andy Bell's talk, 'Be the browser's mentor, not its micromanager'.

It was a revelation.

During the talk Andy makes a website that looks good at every screen size. The transitions are smooth, the text and spacing always look right. And there are no breakpoints.

That's right - no breakpoints.

To get this result Andy uses multiple approaches and techniques: fluid type, fluid space, flexible layouts and CUBE CSS. It took me a while to understand each part and how they all fit together to create a fluid website. But after building a few sites with Andy's approach I found there's less to design and less code to write.

To help you start building your own fluid websites, I'll share some of the lessons I learned by showing you how to recreate a simple hero section - going from clunky breakpoints to a fluid design.

Where I started: Breakpoints, breakpoints, breakpoints

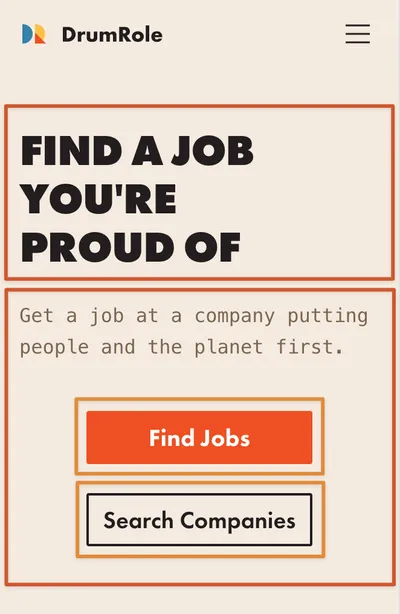

For the example I'll use the hero section from DrumRole, a site I designed and built. This is how it looked at different screen sizes using breakpoints:

Where I ended up: Fluid design

Using fluid type, fluid space, flexible layouts and CUBE CSS I now have a fully responsive hero section that looks good at every size:

How I went from clunky to butter smooth

To begin with I was using Tailwind, which comes with a set of breakpoints. This was the code from the DrumRole hero section:

<section class="grid grid-cols-1 gap-6 max-w-lg mx-auto md:max-w-7xl lg:grid-cols-2 lg:gap-12 xl:gap-16">

<h1 class="font-futura font-extrabold uppercase tracking-tight text-4xl sm:text-5xl md:text-6xl md:max-w-xl md:mx-auto lg:text-7xl xl:text-8xl">

Find a Job You're Proud Of

</h1>

<div class="md:self-center md:justify-self-center md:max-w-md xl:max-w-xl">

<p class="text-brown pb-10 leading-relaxed sm:text-lg sm:leading-relaxed lg:text-xl lg:leading-relaxed xl:text-2xl xl:leading-relaxed">

Get a job at a company putting people and the planet first.

</p>

<div class="w-max mx-auto grid grid-cols-1 gap-y-6 justify-items-stretch sm:grid-cols-2 sm:gap-x-12">

<a href="/jobs" class="font-futura font-bold text-center text-xl text-white bg-orange rounded-sm py-2 hover:bg-black transition-colors xl:text-2xl xl:py-3">

Find Jobs

</a>

<a href="/companies" class="font-futura font-semibold text-center text-xl rounded-sm px-3 py-1.5 border-black border-2 hover:bg-black hover:text-white transition-colors xl:text-2xl xl:px-4 xl:py-2.5">

Search Companies

</a>

</div>

</div>

</section>If you're not familiar with Tailwind, each class prefixed with sm:, md: etc is applied at a breakpoint beginning at a specific screen width. The design is mobile first, so the initial styles are for the mobile design, which is then altered at each breakpoint. In all, there are five steps in the design:

- Mobile design

smbreakpoint beginning at 640pxmdbreakpoint beginning at 768pxlgbreakpoint beginning at 1024pxxlbreakpoint beginning at 1280px (the Desktop version)

The changes I made at the different breakpoints were to do two main things as the screen width grew:

- Increase the size of text and space.

- Move sections around (like how the text and buttons are below the headline on mobile, and move beside it on desktop).

I'll go through both, starting with increasing text and space.

Part One: Making things bigger

The technique to increase the size of text and space is the same, so I'll use the main headline as an example. That's this part of the code:

<h1 class="font-futura font-extrabold uppercase tracking-tight text-4xl sm:text-5xl md:text-6xl md:max-w-xl md:mx-auto lg:text-7xl xl:text-8xl">

Find a Job You're Proud Of

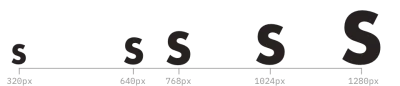

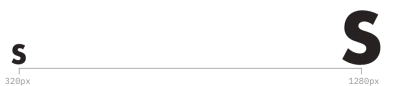

</h1>As you can see, five text- classes are applied to the h1 element, which increases the size of the font at different screen widths:

text-4xl= 2.25rem (36px) is the initial sizetext-5xl= 3rem (48px) from 640px screen widthtext-6xl= 3.75rem (60px) from 768px screen widthtext-7xl= 4.5rem (72px) from 1024px screen widthtext-8xl= 6rem (96px) from 1280px screen width

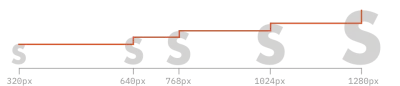

The reason the heading looks clunky as the screen width increases is that the font sizes are static for large parts, then increase in steps.

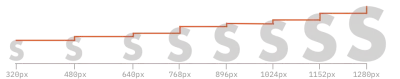

To help make the transitions smoother I could add more font sizes at additional breakpoints. This would shorten the length of the static steps and reduce the size of the increments.

But if I add more breakpoints I also need to make designs for all parts of the hero section at each new breakpoint, and add custom breakpoints and font sizes to my code.

That's a lot of work.

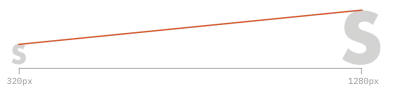

Let's take a step back. At a minimum, I need one design for mobile and one for desktop - and I know what size my heading should be at those two screen sizes:

Why can't I simply take the shortest path between these two points?

If I place the fonts on the bottom line, extend it, and then add a vertical line, it starts to look a lot like a maths problem:

I can use the line, represented by a linear equation, to dictate what size the font should be at every screen width.

I'll explain how this works in detail below - and then provide you with an excellent resource that does all the calculations for you.

Using maths to make our design decisions

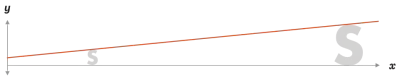

For a website the x axis is the width of the browser window, and the y axis is the size of the font (or space).

As I know what size I want the font to be at the widths of 320px and 1280px, I can calculate the slope of the line:

y = ax + b

a = rise / run = (96 − 36)/(1280 − 320) = 0.0625

∴ 36 = (0.0625 × 320) + b

∴ b = 36 − 20 = 16

∴ y = 0.0625x + 16

I can implement this in websites using the CSS clamp function, which clamps a middle value between minimum and maximum values.

The equation of the line will be the middle value, but I need to make one adjustment first. In my equation x is screen width, but in CSS the screen width is represented by the viewport width, which uses a different scale. There are 100vw for each x. Also, as vw is a relative unit, I should also convert the pixels to rem (1rem equals 16px).

With these changes, the equation for the line becomes:

6.25vw + 1rem

Putting it all together, I can style my heading with:

h1 {

font-size: clamp(2.25rem, 6.25vw + 1rem, 6rem);

}And voilà, my heading is always the right size, and I've only had to make two designs and one style - not five designs and five styles!

Don't calculate this yourself, use Utopia

While I didn't use any breakpoints, the thought of calculating linear equations for every font size, piece of padding, margin, etc., is enough to drive someone to using breakpoints.

Luckily we don't have to because James Gilyead and Trys Mudford built the excellent tool Utopia.

Not only does Utopia calculate all the sizes for you, it uses scale steps to provide a spectrum of type and space sizes. When you pick the ratios for your design you'll get a set of CSS variables to use in your site. So there's no need to remember the equations, just refer to the variables.

Part two: Getting the layout right

In the DrumRole hero section there are two layout changes:

- The main layout, where the text and buttons move from below the heading to the right of it.

- The buttons changing from one on top of the other (stacked) to beside each other.

This is a common pattern - related parts of the page are stacked on top of each other on mobile, then move next to each other on larger screens.

In the hero section I did this using CSS grid. The grid was initially 1 column for mobile, so the two elements were stacked one on top of the other, then I switched to two columns at a specific breakpoint (lg for the main layout, sm for the buttons) to place the items beside each other.

<!-- The main layout (point 1 above) -->

<section class="grid grid-cols-1 gap-6 max-w-lg mx-auto md:max-w-7xl lg:grid-cols-2 lg:gap-12 xl:gap-16">

<!-- rest of the code -->

<!-- The buttons (point 2 above) -->

<div class="w-max mx-auto grid grid-cols-1 gap-y-6 justify-items-stretch sm:grid-cols-2 sm:gap-x-12">

<!-- rest of the code -->But as Andy's explains in his talk, instead of using breakpoints to instruct the browser exactly what to do when, we can give the browser guidelines to adapt the layout based on the available width and height.

But for this to work I had to be more creative in my use of flexbox and grid.

I'll do my best to give an explanation of what I did, but to learn the concepts properly check out Josh Comeau's excellent guides to flexbox and grid, and Heydon Pickering & Andy Bell's Every Layout.

Flexible flexbox

For the hero section, I ditched Tailwind and wrote my own CSS. The HTML structure didn't change, but I replaced the Tailwind classes with my own.

<section class="region with-sidebar hero">

<h1>

Find a Job You're Proud Of

</h1>

<div class="hero__details">

<p>

Get a job at a company putting people and the planet first.

</p>

<div class="hero__buttons">

<a href="/jobs" class="button button-primary">

Find Jobs

</a>

<a href="/companies" class="button button-secondary">

Search Companies

</a>

</div>

</div>

</section>To structure the CSS I'm using Andy's preferred method, CUBE CSS. On the <section> tag, the region is a utility class, the with-sidebar a composition class, and hero a block class.

I'll focus on the styles responsible for changing the main layout, the with-sidebar and hero classes.

.with-sidebar {

display: flex;

flex-wrap: wrap;

gap: var(--_sidebar-gap, var(--space-s-m));

}

.with-sidebar > :first-child {

flex-grow: 1;

}

.with-sidebar > :last-child {

flex-basis: 0;

flex-grow: 666;

min-inline-size: var(--_sidebar-min-size, 50%);

}

.hero {

--_sidebar-gap: var(--space-m-l);

--_sidebar-min-size: 51%;

}The design of the sidebar comes directly from Every Layout. In it, we use the with-sidebar class on a container (the <section>) with two children. The first child is the heading, the second another container holding the text and buttons.

By making the <section> a flexbox, and adding flex-wrap: wrap;, the two children will be placed next to each other when there is space, and will wrap onto a new line if there's not enough horizontal space. The other styles, applied to the children, control how they increase in size when there is available space, and when they wrap.

By giving the second (last) child a much higher flex-grow value it will grow to fill any available space. And by setting a minimum inline size (minimum width), the children will stack if there's not enough space for the second child to fill at least 51% of the screen (a pedantic value, but I was convinced it looked better than the default 50%).

So they're next to each other when they can be, and stacked when there's not enough space. Just what I wanted.

If you read Josh's guide to flexbox, you'll also learn how to use flex-basis to set the width of flex items, which will determine when and how they stack and sit next to each other.

Before I understood flexbox I mostly used it for aligning things. But with a few tweaks I now have a truly flexible and fluid layout.

Flexible grid

Initially I tried using flexbox for the layout of the buttons as well, but couldn't make them the same width. They were only as wide as their content.

This might have been ok, except it made the secondary button too large and prominent. So I needed to find another solution.

When I was using grid in Tailwind, I thought of it as a static thing with a defined number of columns, or rows, or both. To change it I had to explicitly state how many new columns (or rows) I wanted. I wasn't aware that a grid could be dynamic, adapting the number of columns or rows based on the content and available space:

.hero__buttons {

display: grid;

gap: var(--space-m-l);

grid-template-columns: repeat(auto-fit, 250px);

}In the hero__buttons class, the grid-template-columns is doing the heavy lifting. What this says to the browser is, make as many columns as you need (repeat), as long as they're at least 250px wide.

Now, if there is enough space for both buttons and the gap, there will be two grid columns and the buttons will sit next to each other. When there isn't enough space the auto-fit tells the browser to wrap onto a new row, so there will be one column, and the buttons will be stacked. And since both columns are identical, the buttons will be the same width. Perfect.

Ok, so what are the tradeoffs?

Everything has tradeoffs - you can't have it all. And as far as I can tell the main tradeoff with building fluid websites is that you can't control every aspect. At some screen sizes it won't look exactly as you wished it did.

Which, if you're chasing "pixel perfection", could be a problem.

But, in my view at least, aiming for "pixel perfection" is striving for a false sense of control. Yes, you can create a website that matches the design pixel for pixel at the screen width of the design, giving you a sense of the website looking perfect, but who will see it at that screen size?

Probably not as many people as you think.

The team at Set Studio found the ideal viewport doesn't exist. In a 48 hour experiment, they gathered over 120,000 datapoints and found people were using over 2,300 unique viewport sizes. They also included some statistics for common breakpoints, like the percentage of all responses using some of the breakpoint sizes I was originally using for the DrumRole hero section:

- 768px: 0.42%

- 1024px: 0.31%

- Between 1200 - 1300px (I used 1280px): 2.14%

Two of the designs I worked on were likely seen by less than 1% of people. And even if we're generous and include the entire range for the largest breakpoint, even though 1280px is at the top end, less than 3% of people would have seen three of my designs exactly as I intended them.

So I never need to use breakpoints again?

Well, it depends.

If you keep your designs simple and uncluttered, you can make a fully responsive website without breakpoints. This site is a good example - it has zero breakpoints.

But sometimes you'll want to make a specific change you can't do with flexible layouts, like switching between a dropdown button and a row of links in a nav bar. The good thing is this only requires a single breakpoint to switch from/to the button, and you can use fluid fonts, fluid space and flexible layouts to handle the rest.

Wrapping up

I hope this introduction to fluid websites encourages you to give them a go. Fluid type, fluid space, flexible layouts and CUBE CSS do take some getting used to. But when you do, you'll be amazed at how much they simplify responsive design. How much less code you'll write. And how much better your sites look.